Last updated on May 14th, 2022 at 02:37 pm

Similar to my article about energy drinks, this one will be discussing something that I often get asked.

That is: “Are artificial sweeteners bad for you, Mike?”

And, as you may know, I broke down the “Are Energy Drinks Bad For You?” article in a pretty lengthy long-form researched based article; and this may very well come to that as well.

We’ll see how much we can cover and try to stick to the point!

As always, we’re going to have to start off by giving some descriptions of what we’ are actually talking about (for those of you who may not know).

What Are Artificial Sweeteners?

When you look up “what are artificial sweeteners?”, Google automatically brings you to the definition of “sugar substitutes”, which they tell us are:

A sugar substitute is a food additive that provides a sweet taste like that of sugar while containing significantly less food energy than other sweeteners, making it a zero-calorie or low-calorie sweetener. Some sugar substitutes are produced naturally, and some synthetically.

Going a bit further for another definition, MayoClinic tells us this about artificial sweeteners:

Artificial sweeteners are synthetic sugar substitutes. But they may be derived from naturally occurring substances, such as herbs or sugar itself. Artificial sweeteners are also known as intense sweeteners because they are many times sweeter than sugar.

Artificial sweeteners can be attractive alternatives to sugar because they add virtually no calories to your diet. Also, you need only a fraction of artificial sweetener compared with the amount of sugar you would normally use for sweetness.

Are we all clear on this?

I hope so. Because we’re moving on to the specific sweeteners we’ll be talking about.

We’ll refer to them as “the big five”.

The “Big Five” Sweeteners

For the sake of this article we’ll be looking at the most frequently used artificial sweeteners, which I decided we are calling “the big five”.

These “Big Five” sweeteners are:

- Acesulfame potassium

- Aspartame

- Sucralose

- Saccharin

- Stevia

Still with me?

Artificial sweeteners are in a similar boat with energy drinks, and ironically enough, most energy drinks (especially the low-calorie options) utilize these sweeteners in them.

When I say they’re in a similar boat, though, I specifically am referring to the fact that they are very ambiguous in the exact findings and new research is constantly being published regarding them.

That leaves a lot of uncertainties when it comes to both of them, leaving an open-door for the media to flood out headlines that say these sweeteners are: carcinogenic, capable of causing type 2 diabetes, capable of causing weight gain, and much more!

So please keep all this in mind while I go through this article, and know that I am utilizing outside sources to put this article together (which I will either link to throughout and/or at the end of the article), and this is not an opinion based piece.

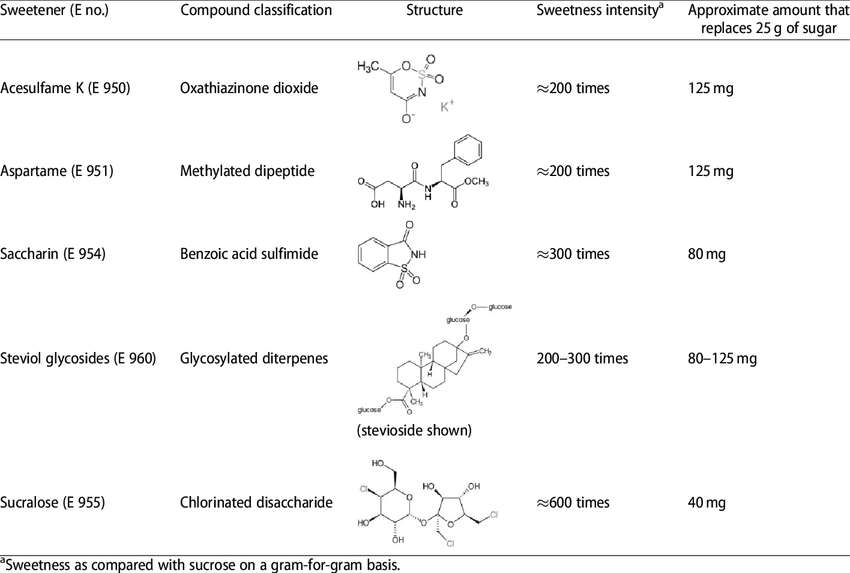

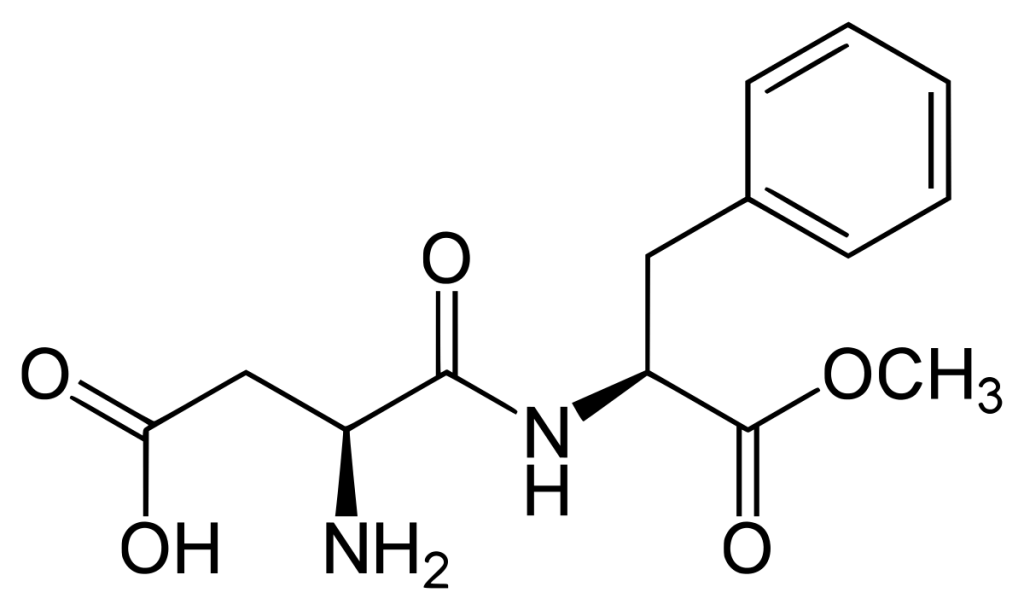

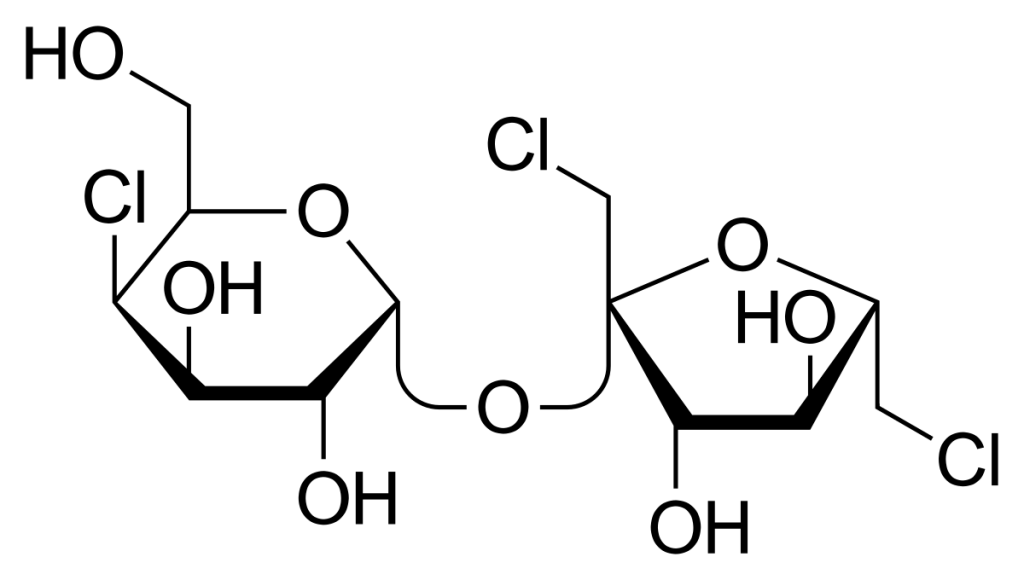

All this being said, I want to continue, but I would also like to mention the fact that artificial sweeteners are often put into one lump package when attacked by the media (again, sometimes similar to energy drinks), but they actually all have a very different make-up (which I will be providing a picture of below – **view the structure**).

For that reason, I’ll be giving some opening information about them as a whole, but then I’ll also be talking about “the big five” individually as well.

FDA Approval and Sweetness Breakdown

So before I continue, I also want to give some information from the FDA and link it to some of the sweeteners we’re going to be talking about.

From there I would like to explain the acceptable daily intake when it comes to these sweeteners, and even show a fun chart on their overall sweetness in comparison to sugar!

In an article from Harvard Medical School they tell us:

The FDA has approved five artificial sweeteners: saccharin, acesulfame, aspartame, neotame, and sucralose. It has also approved one natural low-calorie sweetener, stevia.

We’ll be talking about five of six of these said approvals, not including neotame.

Oh, and here is a list of the artificial sweeteners most commonly used “packaged” names (Source):

- Acesulfame potassium (Sunett)

- Aspartame (NutraSweet or Equal)

- Sucralose (Splenda)

- Neotame (Newtame)

- Saccharin (Sweet ‘N Low)

- Stevia (Stevia

And, while we’re at it, let’s take a look at how sweet these sweeteners are in comparison to table sugar (Source):

- Aspartame: 200 times sweeter than table sugar.

- Acesulfame potassium: 200 times sweeter than table sugar.

- Neotame: 13,000 times sweeter than table sugar.

- Saccharin: 700 times sweeter than table sugar.

- Sucralose: 600 times sweeter than table sugar.

- Stevia: 200-300 times sweeter than table sugar.

Okay, neotame kind of sticks out a bit there, huh?

While the other sweeteners range from 200-700 times sweeter than table sugar, neotame comes in at 13,000 times sweeter!

That just seems absurd.

Acceptable Daily Intake of Artificial Sweeteners

First let’s talk about what acceptable daily intake is.

We’ll go to our friends over at Wikipedia for a definition:

Acceptable daily intake or ADI is a measure of the amount of a specific substance (originally applied for a food additive, later also for a residue of a veterinary drug or pesticide) in food or drinking water that can be ingested (orally) on a daily basis over a lifetime without an appreciable health risk.

Making sense?

It’s basically the safe/recommend maximum amount of a specific substance that you can drink or eat daily over your lifetime without being at any risk.

I’m not even sure if I simplified that or not…

Another note about ADI is how they actually come to the number. It’s interesting to note, because the ADI actually ends up being a number that is much lower than the safe level found. Here’s what Wikipedia continues with:

An ADI value is based on current research, with long-term studies on animals and observations of humans. First, a no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL), the amount of a substance that shows no toxic effects, is determined. Usually the studies are performed with several doses including high doses. In the case of several studies on different effects, the lowest NOAEL is usually taken. Then, the NOAEL (or another point of departure such as a benchmark dose level (BMDL)) is divided by a safety factor, conventionally 100, to account for the differences between test animals and humans (factor of 10) and possible differences in sensitivity between humans (another factor of 10). safety factors with values other than 100 may be used if information on uncertainty about the value of the point of departure (NOAEL or BMDL) justify it. For instance, if the ADI is based on data from humans the safety factor is usually 10 instead of 100. The ADI is usually given in mg per kg body weight.

Big words are big.

Just kidding.

I hope you were able to kind of keep up with that. I wanted to at least source what I was trying to state just before I decided to give you that big excerpt and make your head spin a bit.

Okay. And now for a list of the ADI for “the big five” we are discussing.

ADI for The Big Five:

- Acesulfame potassium: 15 mg/kg/d (30 cans of diet soda)

- Aspartame: 50 mg/kg/d (21 cans of diet soda)

- Sucralose: 5 mg/kg/d (31 splenda packets)

- Saccharin: 5 mg/kd/d (~10 sweet n’low packets)

- Stevia: 4 mg/kd/d (40 stevia packets)

That’s a lot of diet soda and packets of sweeteners, eh?

Well, let’s talk about some of these sweeteners individually now.

Aspartame

Aspartame is the most commonly used artificial sweetener, and one of the most well studied as well.

As I mentioned, it’s roughly 200 times sweeter than table sugar.

The National Cancer Institute gives us a bit more information about Aspartame, stating:

was approved in 1981 by the FDA after numerous tests showed that it did not cause cancer or other adverse effects in laboratory animals.

Aspartame can actually now be found in over 6,000 products around the world, and over two million people consume it on a regular basis.

The American Cancer Society also gives us some more information about how aspartame got a pretty bad name at one point connected to cancer, dating back to a study done during the 1980’s:

One early study suggested that an increased rate of brain tumors in the US during the 1980s might have been related to aspartame use. However, according to the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the increase in brain tumor rates actually began back in the early 1970s, well before aspartame was in use. And most of the increase was seen in people age 70 and older, a group that was not exposed to the highest doses of aspartame, which might also make this link less likely. Other studies have not found an increase in brain tumors related to aspartame use.

As we can tell by that chunk of information, the apparent link to brain tumors was actually voided.

But, the media having it’s own to say about it, continues to make aspartame a villain.

To continue on that, I’ll give you another paragraph from The American Cancer Society, in which they tell us:

In the largest study of this issue, researchers from the NCI looked at cancer rates in more than 500,000 older adults. The study found that, compared to people who did not drink aspartame-containing beverages, those who did drink them did not have an increased risk of lymphomas, leukemias, or brain tumors.

Unfortunately, once the connection is made, a lot of people don’t forget it.

And that’s completely fine. But, it’s nice to know the background.

Final Note:

Studies show that normal adults and children are capable of consuming 50 mg/kg/d, which is equivalent to roughly 21 cans of diet soda, every single day for the rest of your life, with no appreciable health risks.

Sucralose

As I mentioned, sucralose is roughly 600 times sweeter than table sugar.

The National Cancer Institute gives us a bit more information about sucralose, stating:

was approved by the FDA as a sweetening agent for specific food types in 1998, followed by approval as a general-purpose sweetener in 1999. Sucralose has been studied extensively, and the FDA reviewed more than 110 safety studies in support of its approval of the use of sucralose as a general-purpose sweetener for food.

And, like aspartame, they continue that information, describing a shortcoming and “scare” for sucralose, but then explain how that was overturned as well:

In 2016, the same laboratory that conducted the aspartame studies discussed above reported an increased incidence of blood cell tumors in male mice fed high doses of sucralose. However, as with the aspartame studies, FDA has identified significant scientific shortcomings concerning the reported study results.

While not as well known as aspartame, and not having the same links brought to it as often, sucralose is often lumped into the “artificial sweeteners” category. This means, any apparent link that may have been thought at one point, even if that is found voided, puts a bad taste in peoples mouths (see what I did there?), and often times continues to scare people even after.

Final Note:

Studies show that normal adults and children are capable of consuming 5 mg/kg/d, which is equivalent to roughly 31 packets of splenda, every single day for the rest of your life, with no appreciable health risks.

Acesulfame potassium, Saccharin, and Stevia

Okay, so I want to quickly wrap up this section of talking about each individual sweetener in our big five and then move on to talk about weight loss and diabetes in relation to these sweeteners.

I’m lumping these together because these sections were mainly about whether or not these sweeteners are carcinogenic, and I can touch on each of these rather quickly.

The National Cancer Institute has this to say about Acesulfame potassium and Saccharin:

- Acesulfame potassium (also known as ACK, Sweet One®, and Sunett®) was approved by the FDA in 1988 for use in specific food and beverage categories, and was later approved as a general-purpose sweetener (except in meat and poultry) in 2002.

- Studies in laboratory rats during the early 1970s linked saccharin with the development of bladder cancer, especially in male rats. However, mechanistic studies (studies that examine how a substance works in the body) have shown that these results apply only to rats. Human epidemiology studies (studies of patterns, causes, and control of diseases in groups of people) have shown no consistent evidence that saccharin is associated with bladder cancer incidence.

- Because the bladder tumors seen in rats are due to a mechanism not relevant to humans and because there is no clear evidence that saccharin causes cancer in humans, saccharin was delisted in 2000 from the U.S. National Toxicology Program’s Report on Carcinogens, where it had been listed since 1981 as a substance reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen (a substance known to cause cancer). More information about the delisting of saccharin is available in the Report on Carcinogens, Fourteenth Edition.

Again we see a pretty scary link made from an artificial sweetener to cancer.

Add all this up, put the artificial sweeteners in a big bag and mix them up into one general term, and of course people are going to be scared.

But, again, all this information I’m sharing is coming from the National Cancer Institute and other reliable sources.

Moving onto stevia..

I wanted to briefly discuss this one because right now it’s fairly new.

It is a natural calorie sweetener, so it’s actually been taken rather well among artificial sweeteners.

But, I want to mention: just because something is natural does not mean it’s “good”. A compound is a compound. There are things out there, even in fruits (such as apple seeds containing cyanide…and cyanide can kill you…) that are “natural”, but not “good”.

Just a quick note…

Not to say stevia isn’t good, but it’s always nice to have a little natural disclaimer.

I would also like to share one thing about Stevia from Wikipedia regarding the legality behind it and confusing nature of it’s FDA approval:

The legal status of stevia as a food additive or dietary supplement varies from country to country. In the United States, high-purity stevia glycoside extracts are generally recognized as safe (GRAS) since 2008 and allowed as ingredients in food products, but stevia leaf and crude extracts do not have GRAS or Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval for use in food. The European Union approved stevia additives in 2011, while the people of Japan have widely used stevia as a sweetener for decades.

But these are all just things to consider.

Final Note:

Studies show that normal adults and children are capable of consuming ADI that are equivalent to 30 cans of diet soda for acesulfame potassium, a little over 10 packets of sweet n’low for saccharin and 40 packets of stevia, every single day of your life (individually, not combined totals) with no appreciable health risks.

Weight Gain and Type 2 Diabetes

Okay, so this, again is similar to energy drinks in the sense that artificial sweeteners get a bad rap when it comes to them being thought to cause weight gain.

Right off the bat I’ll share some of the health BENEFITS that Mayo Clinic lists for artificial sweeteners:

Artificial sweeteners don’t contribute to tooth decay and cavities. Artificial sweeteners may also help with:

- Weight control. Artificial sweeteners have virtually no calories. In contrast, a teaspoon of sugar has about 16 calories — so a can of sweetened cola with 10 teaspoons of added sugar has about 160 calories. If you’re trying to lose weight or prevent weight gain, products sweetened with artificial sweeteners may be an attractive option, although their effectiveness for long-term weight loss isn’t clear.

- Diabetes. Artificial sweeteners aren’t carbohydrates. So unlike sugar, artificial sweeteners generally don’t raise blood sugar levels. Ask your doctor or dietitian before using any sugar substitutes if you have diabetes.

There was also another study done that…well, I”ll share their words with you:

There was also another study done that…well, I”ll share their words with you:

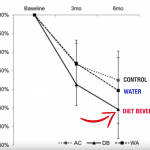

We compared the replacement of caloric beverages with water or diet beverages (DBs) as a method of weight loss over 6 mo in adults and attention controls (ACs).

And, the result:

In an intent-to-treat analysis, a significant reduction in weight and waist circumference and an improvement in systolic blood pressure were observed from 0 to 6 mo.

You can also click the shared picture from this study (on their site or here) and it will enlarge to show the diet sodas (with the inclusion of artificial sweeteners, were determined to be as effective as water for inducing weight loss.

So why do people think artificial sweeteners make you gain weight?

This is actually a very controversial subject.

Psychology Today writes:

Appetite and food intake in the short term: Results on whether artificial sweeteners increase hunger to lead people to eat more in the short-term were completely mixed. A total of 21 studies asked whether artificial sweeteners increased appetite: 10 studies described an increase in appetite and food intake and 11 studies described a decrease in appetite and food intake.

But, the thing to remember is: talking about appetite suppression and hunger is MUCH different than talking about something being a direct cause of weight gain.

While artificial sweeteners make things sweet (obviously), and diet sodas and energy drinks ARE sweet; the argument is that their sweetness can actually lead to your brain wanting more.

Whether or not you actually eat more is your choice, and it’s not actually the sweetener, diet soda, or energy drink causing the weight gain.

So, for example, if you’re counting your calories, and don’t even over, you will still lose weight while utilizing these things.

Another thing that leads to this belief is unfortunately reverse causality.

Obese people generally tend to utilize zero calorie beverages and foods, which in turn are often using artificial sweeteners. This gives the reverse causality that these things are causing the obesity. Similar to the study we saw effect the reputation of aspartame.

This one isn’t as significant as the actual argument for them indirectly causing weight gain, but it is something to think about if you’re currently afraid artificial sweeteners might cause you to gain weight (or stop you from losing weight).

A final thought might be to help yourself by using other methods that can help with appetite suppression. For example, I like to utilize intermittent fasting every single day which I’ve now developed into over eighteen hours of fasting a day where I don’t get hungry in the slightest.

Sometimes it’s control, and other times it is slowly but surely creating new habits and getting used to things.

I hope you guys enjoyed this overview of artificial sweeteners, and I hope it answers some of your questions about them. Obviously there are tons of other studies and things that can be said about them and we are constantly learning more, but this should be a nice start for their background and more.

#####

Mike

SHJ’s Nick Fury

Check out The Superhero Academy and start unleashing your inner SuperHuman.

SUPERHUMAN SECRETS V.2

NOW UPDATED AND EXPANDED WITH A NEW SECTION & SEVEN BONUSES

USD$29 USD$14.95